Alabama Doctor Charged with $6 Million Telemedicine Health Care Fraud Scheme

![Image: [image credit]](/wp-content/themes/yootheme/cache/58/xdreamstime_xxl_134047830-scaled-58ad8ac5.jpeg.pagespeed.ic.TQhjyx0Ebt.jpg)

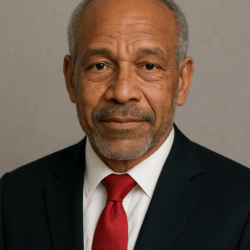

The recent health care fraud charges against Alabama physician Tommie Robinson highlight an escalating compliance crisis in telemedicine-enabled durable medical equipment (DME) and genetic testing referrals. Robinson, who has agreed to plead guilty, is accused of approving over $6 million in medically unnecessary orders between 2018 and 2021, orders that were allegedly generated by telemarketers, devoid of clinical evaluation, and submitted to Medicare through DME suppliers and labs.

This case underscores a persistent and dangerous loophole in Medicare oversight: the decoupling of clinical authority from patient interaction. Telemedicine, when appropriately used, can expand access and streamline care delivery. But when exploited as a documentation conduit, it can become a pipeline for high-volume fraud, especially in categories like DME and molecular diagnostics, where product costs are high and clinical validation is diffuse.

A Familiar Pattern, A Growing Price Tag

According to charging documents, Robinson’s role was to sign pre-filled medical orders for equipment and genetic tests without ever speaking to patients or reviewing their medical histories. These orders were based on telemarketing scripts rather than clinical indications. In doing so, Robinson enabled third-party companies to submit false claims to Medicare for unnecessary services.

This pattern is not new. Similar schemes have proliferated in recent years, often targeting Medicare beneficiaries with offers for free braces or DNA tests, then monetizing their information through fraud networks. A 2022 OIG fraud alert warned of precisely this model: telemarketing-driven referrals funneled through complicit or negligent providers to generate claims for unneeded services.

The financial damage is substantial. A 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) estimated that fraud involving telehealth, DME, and genetic testing accounted for over $1.3 billion in fraudulent claims in just a 12-month period. Yet despite repeated enforcement actions, the fraud model persists, evolving faster than policy and oversight can adapt.

The Weak Link: Clinical Detachment in Virtual Care

At the heart of the issue is the erosion of the clinician-patient relationship in certain corners of telemedicine. Unlike traditional in-person care, where documentation is tied to exam rooms and care continuity, fraudulent telehealth models sever documentation from interaction. Physicians sign off on orders they neither initiate nor review, based on information gathered by marketers or third-party vendors with no clinical accountability.

This breakdown makes fraud detection more difficult. On paper, the claims appear valid, bearing licensed provider signatures, requisite diagnostic codes, and patient identifiers. But in reality, the orders are manufactured and devoid of medical necessity.

Cases like Robinson’s raise broader questions about how CMS, Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs), and private payers verify clinical legitimacy in telehealth-driven services. Current claims adjudication systems are not designed to assess the authenticity of physician-patient relationships or the appropriateness of referrals in real time.

DME and Genetic Testing: High-Reward, Low-Friction Targets

The categories exploited in this scheme, DME and genetic testing, have become consistent targets for fraud, in part because of their billing characteristics. DME orders can yield high reimbursement with minimal follow-up, while molecular diagnostics often command thousands of dollars per test.

Genetic tests in particular pose a unique challenge. Their utility is often probabilistic, population-specific, and dependent on clinical context that is hard to capture in a single claim. Without direct patient consultation, the risk of inappropriate or duplicative testing increases dramatically. A 2024 GAO report found that over 40% of Medicare claims for genetic testing lacked adequate supporting documentation when audited retrospectively.

The same is true for orthopedic braces, mobility aids, and other commonly targeted DME products. Fraudulent actors exploit the fact that these items can be shipped and billed quickly, often without verification of patient need, functional limitations, or trial-and-error fit processes typically documented in traditional clinical workflows.

Telehealth Accountability in a Post-Pandemic System

The Robinson case comes at a time when policymakers are still evaluating which telehealth flexibilities granted during the COVID-19 pandemic should be made permanent. Expanded provider eligibility, looser originating site requirements, and payment parity were all critical to preserving access during the emergency. But they also created new exposure points.

This case underscores the need to differentiate between clinically sound virtual care and commoditized documentation mills. As CMS and Congress consider future telehealth regulations, tightening guardrails around telehealth-driven referrals, particularly for high-cost, low-touch services, should be a priority.

This includes enhanced requirements for documented patient contact, audit trails that validate real-time interaction, and exclusion of providers who demonstrate repeated billing anomalies. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has previously called for such measures, including flagging outlier providers and imposing prepayment review in high-risk categories.

Strategic Implications for Health Systems and Payers

For provider organizations and payers, this case highlights the need for proactive monitoring of referral patterns and documentation integrity. Health systems that contract with virtual care vendors or outsource specialty referrals must ensure clinical appropriateness protocols are not just in place, but actively monitored.

This includes periodic audits of DME and lab orders, verification of patient contact logs, and cross-checking of provider utilization against national and specialty-specific benchmarks. Where third-party telehealth platforms are involved, contractual language must include safeguards around provider credentialing, documentation ownership, and liability distribution.

Insurers, for their part, should invest in AI-enabled surveillance that links ordering patterns, provider relationships, and patient interaction timestamps. Real-time fraud detection must move beyond claim-by-claim analysis toward behavioral profiling, identifying fraud not just by what is billed, but how and by whom.

Restoring Integrity Without Undermining Access

The long-term risk is that repeated abuses of virtual care channels may erode payer confidence and prompt regulatory overcorrection. This could slow innovation in legitimate telehealth programs—particularly those serving rural, aging, or underserved populations who rely on nontraditional access models.

Restoring integrity will require policy precision. Fraud prevention efforts must target specific abuse models, like documentation mills and DME schemes, without chilling legitimate clinical use of telehealth. Cases like Robinson’s should not be viewed as telemedicine failures, but as regulatory failures to distinguish appropriate from predatory use.

As telehealth becomes a permanent fixture in U.S. healthcare delivery, the system must evolve beyond post-hoc enforcement and embrace preemptive validation. The goal is not just to catch fraud after the fact, but to prevent its architecture from forming in the first place.